A Welsh Gate

Who’s Going to Win?

The one with the beer or the one with the schnapps?

Note that flies don’t appear to be attracted to schnapps. Good to know, for when you run out of fly strips.

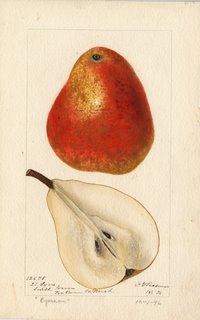

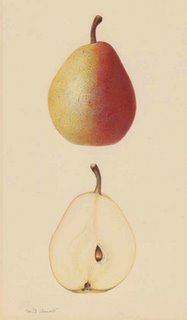

Used to be I was a boy and we grew our pears ourselves. Used to be that I was a young man and I logged those pear trees for firewood, some of them, and grafted others over to red pears, some of them, and pruned the rest. Used to be I was a young father in my first house, and discovered that pear wood burns with a blue flame. Stick a lump of pear wood in a fire and it’s still flaring away like a natural gas fireplace twenty-four hours later. Damn stuff doesn’t go out. Baby laid in the heat on the flame-red carpet, two-inch pile, ‘cuz the house had been redone in the 1960s, you know, why else was it the bargain of the week, $31,000 for two bedrooms, one in deep purple pile, and the baby went to sleep so easy and so fine, in the blue light.

My Greatest Shame

Imagine, the sweetest pear grown in British Columbia, the only one suitable for making fresh juice that did not turn bitter, the only one suitable for drying, and we cut them all down because Safeway and Supervalu could not sell them from an unrefrigerated shelf. Duh. If you want a hint as to what this beauty was like, pick up an Australian or Chilean Packham. There’s some Flemish in there. It’s like riding a bike.

Well time ticks. The baby’s gone off to study linguistics now. She wants to write a dictionary. I used to load up the wheelbarrow with a load of rocks and wheel it around to the front of the house, with her on top, or load it up with a load of pear firewood (Flemish Beauty; you got that right), and set her on top, and wheel her around to the side of the shed. When she slept I’d paint that red house blue, to match the sky, and the sagebrush, and the gravel. They were all blue or grey or grey-blue or blue-grey. The rocks and the gravel came from a hole in the back, where I dug my own septic tank, made a crib inside it with old cedar vineyard posts, because you could do that in that valley. A lot of people used Volkswagens. Volkswagens make a lovely septic tank.

Do Not Approve of Canadian Backyard Sanitation Methods

Crossed arms, crossed leg, crossed fingers, cross looks, cufflinks, ouch.

Used to be that the baby would sit up on the wheelbarrow as I hauled stones around and balance like an acrobat and laugh. Used to be we did everything together.

I’m left with pears.

Beurre Gellert, Ogereau, Painted Lady, Norton Butt.

Listen to the names!

Pierre Cornell, Winter Nelis, Sugar.

Pears are pure poetry. Stick them near a cold storage, though, and they start to taste like a fridge. It’s the volatiles, you see. The volatile gasses. The esters and hormones and all the things about a pear that smell so good. The wind that blows out of a pear orchard one month after harvest. You bite into a pear and it explodes in your mouth and all these angelic scents, these perfumes and alcohols, go up through your sinusses and say God is Here!, and you think, man does this pear taste good. But it’s not taste. It’s smell. That’s the smell that evaporates. Oh, you can keep the flesh nice and crisp, by chilling the things, by replacing the oxygen with carbon dioxide, so they breathe so very, very slowly, so that two months of winter storage becomes six, or eight, or ten. You can replace the carbon dioxide with gas, and extend that even further. You can do whatever you want, but you can’t keep those volatiles in. They’re gone. You want to taste a pear, you gotta go into one of those cold storages and bite the air. The smell of those pears is so thick in the air it stings your eyes. You feel like a bee. Big concrete bunkers like military hangers. That’s where our pears go to die.

Vicar of Winkfield, Teddington Green, Winter Butter.

People used to know what it was about their pears that they loved. People used to have some fun with words. Enough to make you want to study linguistics. Enough to make you want to get out a dictionary and just read the thing.

Adam and Eve After Making The Switch to Artificial Intelligence

(but still nibbling)That’s nice. Want to learn more? Learn more!

Now, the darn things hit the supermarket art installations tasting nice and crisp and juicy and like, well, like the inside of a fridge.

As more and more of the biological engines of Adam and Eve’s world are translated into their technological surrogates, here’s some pear instrumentation you might like to avoid:

Maximum Speed: Walk Away

Used to be that you could dream about pears.

Josephine de Malines, Stinking Bishop, Onward, Doyenne du Comice Pitmaston.

Stinking Bishop!

Used to be that Rob Dawson would phone me up in Hedley, B.C., the old mining town so down on its luck it had managed to survive the whole twentieth century pretty much intact, and ask could I grow him some pear rootstocks, so he could graft some Asian pears onto the things, so the next day I went up to the Agricultural Experimental Station in Summerland and picked them up off the ground, for free, because even then it was 1982 and the whole game was over, we just didn’t know it yet. That was before it became the Agribusiness and Food Experimental Station. Back then in 1982, I picked up those rootstock pears, and set up a bank of lights in my living room, and left it on day and night. In that old mining town, in that old unpainted clapboard house that smelled of cats, that’s how you used to be able to do things.

but Adam has a Nifty Jeep Cherokee

Here’s what the folks at 4X4 B.C. did on Victoria Day Weekend in 2001. And to think it was all hauled out with that wheelbarrow behind the jeep.

Blacksmith, Rumblers, Worcester Black, Dead Boy, Ducksbarn.

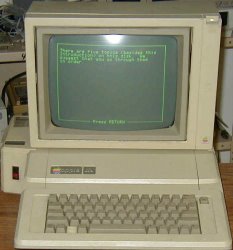

The year I lived in Hedley was the year I bought my first computer. It was an Apple IIe, with a green monitor, disk drive, and a shocking 128k of RAM, for which I paid, for computer, printer, monitor and keyboard, a whopping $2000: a bargain. I had a brother-in-law, see, who got me a special deal. Thank God for that! These little babies are now going for about $50 on eBay, which is pretty great, cuz mine’s still in the garage, right, and last time I checked, a couple years ago, the price was down to, oh, about $5. This is better than Nortel, folks. This stuff is actually rebounding from the fall.

That first year with the Apple IIe was the year the baby pear trees in my porch got brown rot and damped off. I was left with little black threads poking up above the soil, like the wicks of Christmas candles that had burned out. Just as well: those asian pears can’t stand the Similkameen wind.

Late Treacle, Lumber, Merrylegs.

Merrylegs!

Used to be that they grew pears in the Benvoulin area of Kelowna. The best pear land in the world. Well, that’s what we all said. Apples, you see, like to keep their roots dry. Apples are light and full of the sun. Pears, though, they don’t mind the wet. Give a pear tree clay and it nuzzles right on in. Pears and apples and quince, they are all just swelling of the stems, but pears, well, if apples are a leaf, full of water and sugar like a lump of cotton candy at a fair, pears are wood. Each pear is a piece of carved wood. Each pear is a piece of furniture, lovingly waxed and oil and shellacked, with an old cloth, by hand, over and over and over again, each one, and hung up on a tree by wind and light and bees, and each pear tree just keeps producing better and better pears the older and older it gets. Get a knobbled over, blackened pear tree, all bent and hanging down like a sprung umbrella, with the fruiting spurs are gnarled like the spikes of fighting cocks, and broken off, and ending in tiny black buds, and so brittle you brush off against them and they snap off, and the pears from that tree, the pears from that tree will teach you about life. You will taste the snow in those pears, when you pick them. You will know something about living on this earth.

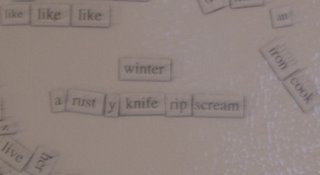

Used to be that apples were valued just as much as pears. Used to be that apples were wood, too. Used to be that people grew russets and cider apples. Used to be that Henry David Thoreau wrote the essay Wild Apples, which he first published in the November 1862 edition of the Atlantic Monthly, to make the claim that only wild apples could contribute to the formation of a country, that grafted, domesticated apples were the ruin of democracy, and, besides, only the wild ones, only the surprising, unkown ones growing behind barns, or in ditches, taste any damn good. Here’s what Thoreau had to say about that.

Before the end of December, generally, they experience their first thawing. Those which a month ago were sour, crabbed, and quite (ooooh) unpalatable to the civilized taste, such at least as were frozen while sound, let a warmer sun come to thaw them, for they are extremely sensitive to its rays, are found to be filled with a rich sweet cider, better than any bottled cider that I know of, and with which I am better acquainted than with wine. All apples are good in this state, and your jaws are the cider-press.

That was in a time when it was wilderness, and a man’s orientation to wilderness, that defined a man.

Now it’s just Red Delicious.

Orally, Anally, Vaginally, this little baby was used in the heydays of torture to extract confessions from reticent confessors. The petals on the bottom of the fruit ensured death by tearing and bleeding.

Christ.

Civilization ain’t always pretty. Now the Benvoulin has been paved over and the Orchard Park Shopping Mall anchors the northern corner of the plot. Now you get to come and shop. You can go there and buy a Christmas tree. You can go there and, gosh sakes, buy a pear.

But don’t look for one of these:

Coppy, Arlingham Squash, Early Griffin, Brown Bess, Gin.

You also won’t find this:

You will find exactly this: Asian pears, each one in a foam balloon; Bartlett pears, from Washington, just the thing that used to grow behind Orchard Park, with the purple leaves in the fall and the pheasants walking underneath the trees, and the wind howling through smelling of the lake; Anjou pears, that’s to say Beurre d’Anjou, but not so buttery, thanks; some Boscs, thin-stemmed like wine glasses, some red pears, either Red Bartletts or, like I grafted in Cawston when I still had a baby and painted my house to match the sky, Red Anjous, with little black knobs of bitterpit under their skins from calcium deficiency; some Forelles, which is to say, Winter Forelles, which is to translate, trout, which are speckled as a trout’s belly and small, tiny — I mean, if a pear is a woman’s pendulous breast, a Forelle is leaning to the young side, to say the least, with its sonnensprossen, it’s freckles brought out by the sun, and its red blush. Just pop the things into your mouth all at once, and they taste like, they taste like Fridge.

Used to be I could walk down the cliff in Naramata, B.C. and pick the Clapp’s Favourites and the Bosc’s and the Comices right off the trees before swimming out from the willows into the sunset, and back, before climbing back up the cliff in the dark, before sitting down with Ezra Pound’s Cantos and reading, "The apricot leaves fall from the east to the west, and I have tried to keep them from falling," and I knew the world, but I didn’t know shit, and I drove away from there, and went to university, instead of buying an orchard and planting pear trees. Now Naramata, one of the series of paradisal planned villages that led the European settlement of western North America, from San Diego and Los Angeles, and north to the Similkameen in 1898 and to Naramata just before the Great War. Now it’s gone digital. Check out the latest apples in the Naramata Parade, complete with police escort. As they say themselves, they needed it.

Oh, it’s all used-to-bes. Or maybe it’s not. Maybe the world is coming back. One pear at a time.

Green Horse, Turner’s Barn, Thorn, Parsonage, Knapper, Pine.

So, when the baby graduated from High School, Harold took her all around Germany and Switzerland, took her to Salzburg, took her to England, and took her to Wales, and on the way to rocky and windy Wales, they drove past little orchards in the Cotswolds, little scrubby plantings of none-too-healthy looking trees planted out on an acre or two on the side of a pasture, and there were signs there, advertising Perry, and so we went into a store and I asked, do you sell Perry. You see, all my life, I’ve wanted to drink some Perry, some pear cider, see, so I asked.

It’s not just me who asked. The folks at the (get ready, it’s a mouthful) London Drinker Beer and Cider Festival of the Campaign for Real Ale, are in full agreement. Here’s Mick, a volunteer, offering the stuff in four pint takeaway size. Thanks, Mick. Cheers to you. How, exactly, did you get that job, anyway? Or check out this link. Man, there’s a guy who loves his pears.

Yeah, they sell pear cider in British Columbia. They sell Okanagan Pear Cider and Growers Pear Cider, which is nice and sweet, made out of Bartletts, and bubbles, and has those esters, eh, those perfumes and aromatics, and is nice and sweet, eh, and bubbly. No, I didn’t mean that.

I meant something rough. Something like wood.

There’s apple cider, for instance, which they make in British Columbia out of Red Delicious, mostly, out of windfalls and culls, shipped north through the whole Okanagan Valley to Kelowna where they are used in a mad flurry of wasps and your feet sticking to the concrete, big truckloads of fruit, no money in it, a silly waste of water, really, and it tastes nice and sweet eh, and then there’s Calvados.

God let them rest in peace.

So, it’s 1981. We’re in East Kelowna. It’s Christmas. I’ve gone through all the side roads for a week, picking apples off of wild trees. I’ve found an old field down in the Benvoulin, which contains: one horse, three old apple trees, a few old wooden props for holding the branches up, a barbed wire fence, and a mess of wasps. Oh, yeah, and a ditch, and in that ditch a tree, and on that tree an apple that looks like a green tomato, and which tastes like ripe, fresh pineapple, and I take it home, and on Friday night we have an apple tasting, and to set the mood, Hugh brings out the bottle of Calvados.

"Generations of attention went into that bottle," says Hugh’s father, a retired librarian. "To get it so it went glug just like that when you pour it out."

Their husbands were off to the Great War.

They did not come home.

At least Eve got to keep her Adam.

Apple brandy. Burns when it goes down. In German they call it Geist. They make pear geist, too. Ghost. As in: Holy Ghost. The God in the apple. The God in the pear.

The spirit of creation stripped of the world. Eternity.

Ezra Pound did that. When he was in London, he lived right next to the church in Kensington. He used to go out for long walks when the vicar started ringing the bells. Drove him nuts.

Right there in your glass. You can drink it down. Right there. In your glass.

I asked for that in the Cotswolds, for something like that, not Williams Christ Birne Geist. Not at all. Just for Perry.

Flakey Bark, Harley Gum, Nailer, Bastard Sack.

Perry! Well, here’s what I got: one tall green bottle, like a riesling bottle from Alsace, with a long thin neck and a cork, and the proprietress’s favourite, a bit more expensive, mind, 6 pounds instead of the 3,50 for the others, but worth it, she said, not a sparkling Perry, you can have a sparkling Perry, she told me, but a still one.

"What do you recommend?" I asked. "I want the best," I said.

"Take the still," she said, "although it’s a bit more expensive, mind, but worth it."

That night we drank that Perry in Wales.

Winter Butterbirne, Harvest Queen, Early Treacle.

The next morning, my daughter slept late, and I went walking up in the hills, between the stone fences, up onto the heath. A cold wind blew down the valley, off of Snowdon. To the east, the Irish Sea shivered on the shore in a white line of cold. The land was barren, and stark, stripped down, stripped to the bone. Nothing grew there except grass, and rock, and rock and rock and rock, and gates in the rock, which were rocks piled up in a gap in the fence, and if you wanted through, you lifted down the rocks, went through, and lifted them back up again, because you had time for that, obviously, and sheep. Lots of sheep. And heather. And wind.

And then I stepped out of the wind, into a little hollow in the lee of the wind, and it was the land of poetry. It was Robert Graves’ land of poetry. It was wild apple trees, and hawthorns, and rowans and hazelnuts and wild rose, and a stone farmhouse down below with a red door, and the red furze on the hills, and I went back into the house, cold, but I went back knowing it is not all used-to-bes.

It’s not.

The earth is not an art installation. The corollary must, logically, also be true: art is not a fabrication. It is how you live on the earth.

Note the stairs, and, especially, the gate itself: two stones. You lift them up, you step through, you put them back.

Sweet Huffcap, Clapp’s Favourite, Improved Fertility.

Next week: Sneaking Back into the Garden.

Is That Harold In a Cider Apple Tree?