Doing Time

It’s tough to stand in the Garden of Eden and look out.

doG staring out of the Garden of Eden after Adam and Eve hit the road.

Adam and Eve stand in the Garden of Eden in Dresden, and look out and see crowds of tourists who have come to see the Florence on the Elbe, and see Adam and Even staring out instead.

In his book Stealing the Mona Lisa, Darian Leader suggests that’s what we come to see: a mirror. The frame around the picture, whether it’s made of gilt wood or just a wall where a picture used to be, like when the Mona Lisa was stolen in 1911, let’s us know that we’re going to see our soul, and we crowd around like bees to a dandelion. Check out this picture of Mona Lisa tickling herself. That’s the trouble with putting bees out for pollination in a pear orchard: the bees prefer to pollinate the carpet of dandelions, while the butter-white flowers overhead tremble in the breeze.

What happens, though, when you stare back into the Garden of Eden and, doggone it, God’s not right there, staring at you with his sad, sad eyes?

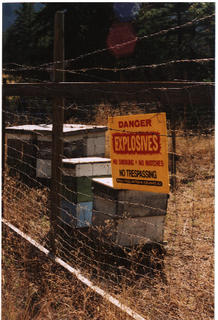

Staring into the Garden of Eden, February 2005, Evelyn B.C.

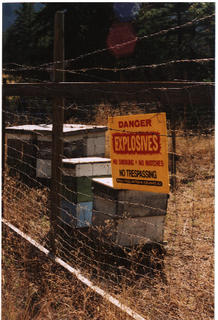

You get another jail, with No Trespassing signs, by the looks of it. On a road west of Smithers, which is west of Evelyn, I once saw one: Before Trespassing Please Notify Next of Kin. Here in Williams Lake I saw another one yesterday, nailed to the vinyl siding of a house looking down over an equipment yard: We Do Not Call 911. Gardening is a private affair, I’d say. Not so for trees. They sprout fruit any old place out of their twigs. In fact, you could say the hormones all get to be too much to contain and out pops the fruit, like balloons.

Quince Popping Out like Balloons.

Okanagan Falls, British Columbia.

Thanksgiving, 2005

Ah, but then, quince, like their sisters apples and pears, are the swollen stem around the womb, which we call the core, which contains five ovaries, each of which holds some black seeds, rounded at one end and pointed at the other, which contain the cyanide, which could lay us low, if we wanted to leave the world in real bitterness. But wait, what’s that?

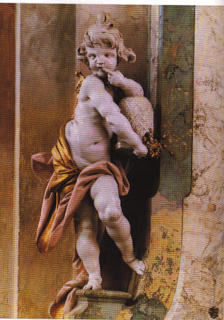

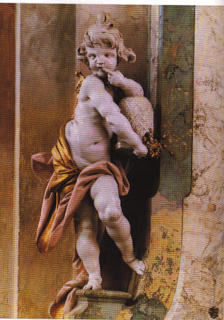

Speaking of pollination, in the church at Birnau above the old lake-houses in Lake Constance at Unteruhldingen, a church which, I might add, is surrounded by pear trees, big old pear trees rising up around the church like whipped cream, cherubs are sprouting out of the walls like quince with rolls of fat and the faces of politicians. Check out this dude:

A Cherub in Birnau, Dipping into the Honeypot

The guidebook talks about a metaphor for the holy spirit. I dunno, folks. I’d say if that’s the case, then I’d say that apple that Adam nibbled at was Eve’s womb. Don’t think so, huh? Check out these two pictures of the Tree of Knowledge in the Garden of Eden, straight from the Cologne Cathedral to you, courtesy of the light from the sun, which Plato, of course, said was God.

Here's what Hamlet's Dad had to say about it:

Hamlet’s Ghost Whispers Sweet Nothings into Hamlet’s Ear

Hamlet: Act I, Scene v.

This pear tree thing, though. I tell ya, it might not be such a good idea to fall asleep in a garden. When I was in the cool underground halls of the German-Roman Museum right next door to the Cologne Cathedral in that hot, hot summer when the corn turned to rustling shooks in the July fields and rattled in the wind like noisy flames made out of the pages of books thumbed through by a bored monk looking for something else, I got God to blink out of my camera, and let this image in of the tree, the serpent, and, wait! That’s not Adam. That’s randy old, goat-legged Pan. Adam, it seems, needed a cold shower. Ha, ha ha! Maybe Adam was the cold shower.

The Serpent Interrupts Pan While Playing on a Flute and Whispers Sweet Nothings in His Ear

I guess these kind of double takes are what you get when you graft one idea onto another. Imagine how a tree feels when it is nobled. First you get out a chainsaw and lop off all the limbs, except for one strong one near the top. Then you clean up the torn edges of the bark with a sharp knife, slit the bark at right angles to the stump, slip in a scion from a different tree, one you like -- a Bartlett pear, perhaps -- nail it down, paint it with tar, or beeswax, or latex, and wait for God’s sun to shine down on it. At first, though, it doesn’t look so noble.

Ouch. But that’s what you do with trees that just don’t bear the fruit you’d like. I suspect that’s why God booted Adam and Eve out of the Garden, too. They had their own ideas. And all their children are trying to get back in. Sometimes they did it with grafting. Sometimes they did it with just a tad more brazenness than that.

Adam getting ready to leave the garden and settle the wilderness.

Take the Bartlett pear, for example. Until this guy called Bartlett imported it to North America, it was a European variety, called Williams, and in Europe it’s still sold as that. If you mention a Bartlett pear to the folks over in Belgium or Holland or France they’ll just stare back blankly, but Williams, ah Williams: Williams is the pear of pears. Sometimes, you see, the Garden of Eden is a matter of marketing.

In his inaugural lecture to the chair of poetry at Oxford in 1850, Matthew Arnold wrote:

Arnold had in mind a deliverance from faith, morality, and superstition. You could have said as well, that he had in mind deliverance from the poetry of romantic poets like Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who was very much interested in questions of faith, morality, and superstition:

The pears I grew up with, Bartletts, were shipped to the Keremeos Packing House, from where the socialized marketing system sold them around Canada and the world, for 3 cents a pound. It cost 10 cents a pound to grow the pears.

These were the same pears used to make schnapps in Germany and France: Williams, or, in German, Williams Christbirne, which translates as William’s Lord of Pears, or William’s Pears of Christ. Old man Bartlett had them brought over to New England in 1812, grafted them, and renamed them after himself. Bartletts eventually made it to California in 1849, during the Gold Rush. Forty years later they made it to Upper Keremeos, British Columbia, planted out in a bend of the Keremeos River, back in the days when the world was big and before it got downgraded to Keremeos Creek. In the year the war ended in Vietnam, Bartletts from Keremeos were loaded illegally onto broken-down trucks in the night and hauled to Northern Alberta, along a network of renegade wholesalers and grocery stores, like the Underground Railroad that brought escaped slaves to freedom in Canada. Trucks crashed, bills weren’t paid, and the pears returned 3 cents a pound.

What the Christians said is there was no chair, only God.

What Einstein said was God does not play dice. What he meant was that quantum theory was pretty whacked. He figured we hadn’t quite figured it out yet. Of course, Einstein was right.

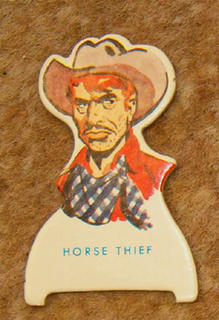

What God Actually Played When He Didn’t Play Dice: Cheyenne.

Why, you’d think God used to live inside a fence or something, right?

God’s Bees from Birnau (Pear Meadow), Brought to the New World.

Bang, bang, you’re dead.

God!

Look at him. Just Look at him learn to be the ghost in the machine!

Next Week: Quantum mechanics, Dolly (who was old before her time), and how to think like a computer.

Adam and Eve stand in the Garden of Eden in Dresden, and look out and see crowds of tourists who have come to see the Florence on the Elbe, and see Adam and Even staring out instead.

In his book Stealing the Mona Lisa, Darian Leader suggests that’s what we come to see: a mirror. The frame around the picture, whether it’s made of gilt wood or just a wall where a picture used to be, like when the Mona Lisa was stolen in 1911, let’s us know that we’re going to see our soul, and we crowd around like bees to a dandelion. Check out this picture of Mona Lisa tickling herself. That’s the trouble with putting bees out for pollination in a pear orchard: the bees prefer to pollinate the carpet of dandelions, while the butter-white flowers overhead tremble in the breeze.

What happens, though, when you stare back into the Garden of Eden and, doggone it, God’s not right there, staring at you with his sad, sad eyes?

You get another jail, with No Trespassing signs, by the looks of it. On a road west of Smithers, which is west of Evelyn, I once saw one: Before Trespassing Please Notify Next of Kin. Here in Williams Lake I saw another one yesterday, nailed to the vinyl siding of a house looking down over an equipment yard: We Do Not Call 911. Gardening is a private affair, I’d say. Not so for trees. They sprout fruit any old place out of their twigs. In fact, you could say the hormones all get to be too much to contain and out pops the fruit, like balloons.

Okanagan Falls, British Columbia.

Thanksgiving, 2005

Ah, but then, quince, like their sisters apples and pears, are the swollen stem around the womb, which we call the core, which contains five ovaries, each of which holds some black seeds, rounded at one end and pointed at the other, which contain the cyanide, which could lay us low, if we wanted to leave the world in real bitterness. But wait, what’s that?

The quince has thorns, too!

It might have been that Christ wore these things around his head when he carried the intersection of the sacred and spiritual worlds on his shoulders up to the mountain where he was nailed up with the other thieves. Sheesh.

Speaking of pollination, in the church at Birnau above the old lake-houses in Lake Constance at Unteruhldingen, a church which, I might add, is surrounded by pear trees, big old pear trees rising up around the church like whipped cream, cherubs are sprouting out of the walls like quince with rolls of fat and the faces of politicians. Check out this dude:

The guidebook talks about a metaphor for the holy spirit. I dunno, folks. I’d say if that’s the case, then I’d say that apple that Adam nibbled at was Eve’s womb. Don’t think so, huh? Check out these two pictures of the Tree of Knowledge in the Garden of Eden, straight from the Cologne Cathedral to you, courtesy of the light from the sun, which Plato, of course, said was God.

Pear-shaped Mary and Her Ovaries Hard at Work

Cologne Cathedral, 2003

On the left, Mary has all the saints in their nests in her sacred tree.

On the right, they are peeking out of her skirts like chickies under a mother hen.

Check out Hamlet’s father lying down underneath the tree, waiting for a serpent to poison him in the ear!

Here's what Hamlet's Dad had to say about it:

Sleeping within my orchard,

My custom always of the afternoon,

Upon my secure hour thy uncle stole,

With juice of cursed hebenon in a vial,

And in the porches of my ears did pour

The leperous distilment; whose effect

Holds such an enmity with blood of man

That swift as quicksilver it courses through

The natural gates and alleys of the body,

And with a sudden vigour doth posset

And curd, like eager droppings into milk,

The thin and wholesome blood: so did it mine;

And a most instant tetter bark'd about,

Most lazar-like, with vile and loathsome crust,

All my smooth body.

Thus was I, sleeping, by a brother's hand

Of life, of crown, of queen, at once dispatch'd:

Cut off even in the blossoms of my sin

Hamlet: Act I, Scene v.

This pear tree thing, though. I tell ya, it might not be such a good idea to fall asleep in a garden. When I was in the cool underground halls of the German-Roman Museum right next door to the Cologne Cathedral in that hot, hot summer when the corn turned to rustling shooks in the July fields and rattled in the wind like noisy flames made out of the pages of books thumbed through by a bored monk looking for something else, I got God to blink out of my camera, and let this image in of the tree, the serpent, and, wait! That’s not Adam. That’s randy old, goat-legged Pan. Adam, it seems, needed a cold shower. Ha, ha ha! Maybe Adam was the cold shower.

I guess these kind of double takes are what you get when you graft one idea onto another. Imagine how a tree feels when it is nobled. First you get out a chainsaw and lop off all the limbs, except for one strong one near the top. Then you clean up the torn edges of the bark with a sharp knife, slit the bark at right angles to the stump, slip in a scion from a different tree, one you like -- a Bartlett pear, perhaps -- nail it down, paint it with tar, or beeswax, or latex, and wait for God’s sun to shine down on it. At first, though, it doesn’t look so noble.

A Mac Apple Tree Grafted to Granny Smith and Showing the Cosmetic Surgery Scars

Cawston, B.C., 1980

If Michael Jackson were a tree, he might look like this.

Beauty might be in the eyes of the beholder, but it sure is elusive.

Ouch. But that’s what you do with trees that just don’t bear the fruit you’d like. I suspect that’s why God booted Adam and Eve out of the Garden, too. They had their own ideas. And all their children are trying to get back in. Sometimes they did it with grafting. Sometimes they did it with just a tad more brazenness than that.

Take the Bartlett pear, for example. Until this guy called Bartlett imported it to North America, it was a European variety, called Williams, and in Europe it’s still sold as that. If you mention a Bartlett pear to the folks over in Belgium or Holland or France they’ll just stare back blankly, but Williams, ah Williams: Williams is the pear of pears. Sometimes, you see, the Garden of Eden is a matter of marketing.

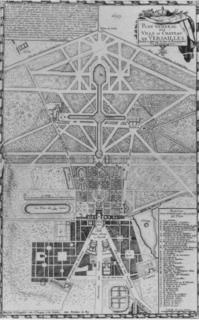

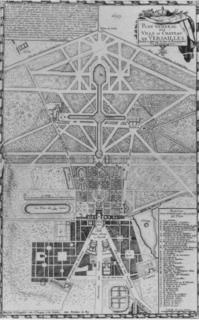

But as my father said once about growing up as a boy during the bombing of Germany during World War II: people are awfully hard to kill. “You can drop bombs on them and they’re still there.”A New Plan for the Garden of Eden. Versailles.

This time, things would be right. This time it was going to be complete with a sun, to walk on, a cathedral, for swans to swim in, and a big arrow to point your way, so you stayed on target.

Adam’s target.

After all, what’s the fun of playing with God if he doesn’t shoot back? Oops, looks like he missed again.

In his inaugural lecture to the chair of poetry at Oxford in 1850, Matthew Arnold wrote:

An intellectual deliverance is the peculiar demand of those ages which are called modern; and those nations are said to be imbued with the modern spirit most eminently in which the demand for such a deliverance has been made with most zeal, and satisfied with most completeness.

Arnold had in mind a deliverance from faith, morality, and superstition. You could have said as well, that he had in mind deliverance from the poetry of romantic poets like Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who was very much interested in questions of faith, morality, and superstition:

’Tis the merry Nightingale

That crowds, and hurries, and precipitates

With fast thick warble his delicious noteds,

As he were fearful; that an April night

Would be too short for him to utter forth

His love-chant, and disburthen his full soul

Of all its music!

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Nightingale, 1798

The pears I grew up with, Bartletts, were shipped to the Keremeos Packing House, from where the socialized marketing system sold them around Canada and the world, for 3 cents a pound. It cost 10 cents a pound to grow the pears.

How the game is played. Easy, huh. No rules, really.

These were the same pears used to make schnapps in Germany and France: Williams, or, in German, Williams Christbirne, which translates as William’s Lord of Pears, or William’s Pears of Christ. Old man Bartlett had them brought over to New England in 1812, grafted them, and renamed them after himself. Bartletts eventually made it to California in 1849, during the Gold Rush. Forty years later they made it to Upper Keremeos, British Columbia, planted out in a bend of the Keremeos River, back in the days when the world was big and before it got downgraded to Keremeos Creek. In the year the war ended in Vietnam, Bartletts from Keremeos were loaded illegally onto broken-down trucks in the night and hauled to Northern Alberta, along a network of renegade wholesalers and grocery stores, like the Underground Railroad that brought escaped slaves to freedom in Canada. Trucks crashed, bills weren’t paid, and the pears returned 3 cents a pound.

What the Christians said is there was no chair, only God.

What Einstein said was God does not play dice. What he meant was that quantum theory was pretty whacked. He figured we hadn’t quite figured it out yet. Of course, Einstein was right.

Why, you’d think God used to live inside a fence or something, right?

Bang, bang, you’re dead.

God!

Look at him. Just Look at him learn to be the ghost in the machine!

Next Week: Quantum mechanics, Dolly (who was old before her time), and how to think like a computer.