Even Dolly Thinks So Too

A month ago, we started out with the poet Al Purdy cruising through B.C. Central Plateau on the lookout for irony.

Al Purdy discovering the Lost Plateau of the Cariboo, his sharp eye on the lookout for Irony.

He found plenty of it. In fact, he found horses, with their reins looped over a rail in front of the grocery store at Lone Butte, while their riders, cigarette smoke pouring out of their orifices like stovepipes sticking every whichway out of a bush shack, went in to pick up some groceries. In other parts of Canada, people were using cars for that kind of thing: both to smoke up the air and to get themselves to it. It was, after all, the 1960s. The country was on the move. Before we knew it, it was 1967, and every primary school class in the country learned to sing about it:

In the Cariboo, though, up high on the Plateau, people found their own use for cars. They stuck to it, too.

Cariboo Lawn Ornaments

Coralling cars on the shore of a Cariboo Lake at 70 Mile, 1992.

Al thought the horses were all pretty funny, and he built a whole literature of irony out of his response to them. Art imitates landscape. There’s enough irony in the Cariboo to keep any functioning society going for years.

It’s not just the Cariboo, though, you know. Look at what the Welsh had to say about it, way back, even before the English moved in:

Art Imitating Landscape in Wales, Ausut, 2003

Here we all were, hunkered down behind our mountains and rivers, happily slipping back to Eden, when Al came into town and ruined it all.

I’m not joking. Two years after Al Purdy wrote The Cariboo Horses, a man received a Canada Council grant to go up on top of Fairview mountain among the blackflies blackflies blackflies and the abandoned mineshafts and write poetry. Canada, like Wales, had a sure and strong desire for poetry in those days. Well, in Canada’s case, it was more a matter of nationalism, but, hey, poetry has proven itself over the centuries as being one heck of a great way to stir up the nationalistic juices. We should have known better, though.

Russian Soldiers Preparing to Defend Their Country in 1914

When the poetry did not come in a Tennysonian torrent, he eventually moved down off of the mountain. That was at the end of the 1960’s, when the poet, Charles Lillard, moved out of the bush and saw a young Tsilq’otin woman riding a horse across the white glacial water of the Taseko River on the western edge of the Chilcotin Plateau. She looked at Lillard with complete disdain. This, too, is called the evolution of nationalism.

Two years after Lillard looked across the Taseko River and saw what was humanly possible, the blackfly poet of the Similkameen was recovering from brain surgery by talking to me slowly in the hot Cawston sun, while I grafted his apple trees. He wanted to plant an orchard for his three-year-old daughter, who would soon survive him. Five years later, cancer invaded Lillard.

Sometimes people in isolated areas get the weirdest ideas. Out in the Irish Sea, off the coast of Wales, lies the Island of Anglesey, where local legend holds that 10,000 saints are buried, where the Christian Church got its start three and a half centuries before it got its legs underneath itself in Rome.

The Island of Ten Thousand Saints.

The tides of the Irish Sea break against it like the waves curling off the bow of a ship. You can just make out Ireland in the background to the right. The shot was taken from a gun emplacement on the Welsh Coast, a bit of memorabilia from the Second World War. You just never knew what was going to pop up. The day I was there, the sun was shining, but I did have to watch where I stood amongst the sheep shit, yes, and on the way out there it seems I was almost run over by a nun, with a determined glint in her eye, as she raced her little blue car along a narrow sheep-shit lined road. There are, it seems, precious few fences in Wales, and when they show up, people don’t rightly know what to do with them. I love Wales.

Some poets like fences, though. Here’s what Matthew Arnold said about them at Oxford, when accepting the chair of poetry:

In poetry? You gotta laugh. Oh, unless Arnold meant this:

Matthew Arnold Delivering His Speech to Oxford

A page from Dean’s Royal Moveable Punch and Judy, a Victorian children’s book (c. 1870)

The people are not amused.

Arnold didn’t have to worry much about what the people thought, perhaps, but we do, these days, because the result of all this irony, all this disconnect between the lives we live and the words we have with which to speak of it, is that we are being replaced. Even the tools I used on the farm as a kid are now turning to rust. Even the computers that are stacked up in the cupboard in my garage and on the landing of my stairs, a precarious pile of slate grey plastic moulding, mouldering like old leaves, has become obsolete. Modernism, the whole industrial project that was going to give us the tools with which to live better, richer lives, is on the way out.

God the Industrialist and his Crew at Oxford,

building Adam in the Garden of Eden

A Souvenir Postcard from the Hermann Denkmal in Germany, c. 1914

Matthew Arnold forgot to save his work.

Now, if you’re anything as lucky as Arnold is with stemming the tide of popular revolution, or, God help you, anything as luck as I am with computers, you will have forgotten, at times, to save your work, too. You, too, will have sat in heart-racing despair as the hard drive crashed and everything you had worked on so hard for the morning had become irretrievable, at worst, or mind-numbingly, time-destroyingly hard to retrieve, at best, when you could have, like, been writing a poem or something, right. You feel so helpless. Really, now, that’s silly. I’ve always said, that every computer needs to come with an emergency kit, like those little red fire alarms in school hallways that someone is always pulling when there is no fire, just to hear the bells ring. It could be covered with a glass plate, and just like those irresistable, strawberry-licorice-coloured jobs in school hallways could say: In Emergency Break Glass. You would not feel so powerless in front of your machines. I figure that’s worth something. I figure that’s worth a lot.

In Emergency Break Glass.

To the winds with planned obsolescence!

The scene that sticks with me from the movie Diner is the one in which Mickey Rourke stops his car at the side of a road when he sees a pretty girl excercising her racehorse behind a white fence. He tries to put the make on her, and asks her name.

No kidding.

On that note, the movie ends.

On that note, five years ago, Shauna told me about a conversation she had had one morning in 100 Mile House, right here on the Plateau. A friend of hers, a working man, a regular guy in a blue cotton work suit you order from the Sears catalogue, had come to her, asking her to give me a message. Shauna tells the story:

No, I can’t. I can tell you about something real.

To noble a pear tree, first select a new shoot the thickness of a pencil from the tree you wish to clone. It will be late July or early August. Trim the leaves on this shoot down to stems 1/2 centimetre in length. This is called your budwood. Second, select a seedling pear tree of approximately the same thickness and cut a T-shaped cut in the bark of the seedling tree, approximately six inches from the ground. The top of the T should be approximately 1/3 the diameter of the tree and the leg of the T approximately three centimetres long. Third, after prying open the two flaps of bark formed where the top and legs of the T meet, hold the budwood in your left hand, with the tip of the wood towards you, and place your knife approximately 1 1/2 centimetres below a bud. Drawing your knife towards you, cut down slightly into the wood; continue drawing the knife until it has cut below the bud to a point 1 centimetre above it. The cut will be easier to make if you draw the knife laterally through the wood at the same time you pull it towards yourself. The cut will only be possible around the hard wood surrounding the bud if the knife is sharp enough to shave with or to cut a loose piece of paper with one light stroke. You might want to take care of that before you start. Complete the cutting of your bud by freeing the bark containing it it by scoring the bark at the top of your cut and lifting the bud free with a sideways motion. Fourth, slide the bud into the opened T on the seedling tree until it fills the cut from top to bottom. If the bud is too long, cut off the protruding part in the cross of the T with your knife. Fifth, beginning at the bottom of the T, wrap the bud snuggly with a 9 cm. length of rubber band, securing it at top and bottom by crossing it over itself in a half-hitch loop. In ten days, the bud will have adhered to the new tree. In two months, the rubber band will rot off. Early the next spring, cut off the seedling tree one half-inch above the top of the bud. When the tree begins to shoot, remove all shoots coming from the original tree, leaving only the shoot growing from the bud you grafted on the summer before. That bud will make your new tree. Depending on variety and rootstock, in about five years it will bear fruit.

Espalliered Pear Tree, Barrington Hall, England, August, 2003

Monkish tricks with pear trees to catch a little more summer sun.

Obsolete knowledge? Perhaps. Just after the First World War, the American poet Ezra Pound wrote his Confucian Canto, poem number XIII in a long series meant to imitate an industrial assembly line. So clever, huh! Pound wanted to write a book of poems which would be required reading for any man wishing for a career in politics. He didn’t know about computers. Or, to put it better, he hadn’t yet learned how to think like one.

It’s not his fault, entirely. After all, he died in 1973, and back then, this is what we knew about how computers think:

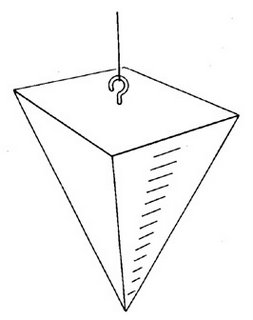

Computer on the Look-Out for its Next Meal

from The Story of Computers, by Roger Piper, Harcourt Brace & World, 1964

Oh, we know better now, I tell you. Now it’s computers that are looking over their shoulders toward replacement. That sledgehammer? That computer emergency kit? It’s too late.

The Obsolesence of the Computer Emergency Kit

Thing is, it’s not our hammer any longer. Thing is, we’re no longer at the pinnacle of evolution, or the top of the food chain. Dolly is. You probably know Dolly. Dolly is the sheep cloned in England, using cells from the uterus of a dead sheep. She grew up to be a handsome, bleating animal, frisky as the day she was born, but, alas, Dolly’s cells were old. It seems that a living cell can only divide so many times before it starts making mistakes, like a computer, might I add. Ah, Dolly had her dreams, there on the top of the food chain.

Dolly At the Top of the Evolutionary Ladder, Enjoying the View

The American composer Steve Reich revisited the sampling techniques and rhythms of his 1980s masterpiece about the Holocaust, Different Trains by composing a new piece in comemoration of Dolly’s plain blind bad luck outside the fence of the Garden of Eden. Instead of sampling trains, German and American, and American conductors and Holocaust survivors, instead of talking about “Black crows, black crows were invading my country. Black crows were invading my country,” in the rhythms of the rails, he sampled scientists speaking about their work with Dolly. “I can’t wait to get a new body,” said one of them. “We are all machines,” said a second. “I have no difficulty with the idea of pulling the plug on any machine,” said another. Reich constructs his music around their voices. Dolly is transformed into a child. It laughs with its mother. Have a look and listen, here. Your life depends upon it.

Dolly Looking Out on a Brave New World

"The American Race!"

Here, you might need this:

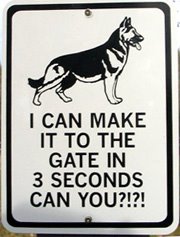

Basic Poetry Reading Tool

On the day Germany declared war on the United States, Ezra Pound urged American soldiers to conquer all of North America, including Canada, and to leave Europe to the Europeans.

Thanks, Ez. Here’s a little something for you, too:

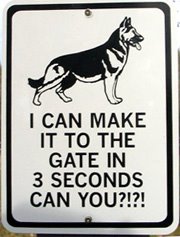

The Archangel Gabriel Does Not Call 911

Hip Dysplasia, though. Check out those bad hips. That’s what inbreeding gives ya.

When Pound made his broadcasts over Radio Rome, unknown to him, unknown to everyone except for three men, the German Post Master General and his assistant had constructed a nuclear bomb in their basement in a Berlin suburb. The third man did not believe them. When the Post Master General brought the idea before him, Hitler scoffed, and said, “Oh, now my Postmaster is going to tell me how to win the war!” The idea was that the A10 Rocket could carry it across the Atlantic and drop it on New York. It would have won the war, all right.

Tune back next week for some speculation on that and on the Byzantine politics of Aryan Physics. Aryan physics? God, yes.

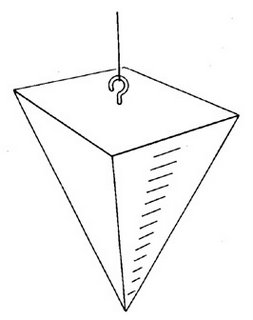

Computer Built in Accordance With the Analogical Laws of Aryan Physics

If you fill a vessel with water to a specified level, then lower this cast pyramid into it to a predetermined mark, you can read off of it the cube root corresponding to the volume of water displaced by the pyramid. For this, you don’t need Quantum Physics.

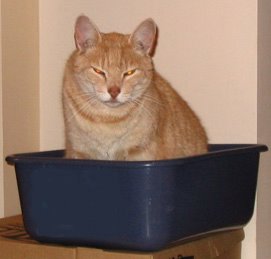

Your host next week, that Sumo Wrestler of Quantum Physics: Schrödinger’s Cat.

Schrödinger’s Cat is Not Amused

To prove that there was something wrong with regular (aka Aryan) physics, in the 1930s the Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger proposed that a cat randomly killed in a sealed box would appear neither alive nor dead until the box was opened, that, in fact, you could not tell when the cat had died: during the random release of cyanide, or when the box was opened and the cat was observed to be dead (or alive). This, said Schrödinger, was silly. He suggested we needed a better physics.

Even Dolly Thinks So Too

He found plenty of it. In fact, he found horses, with their reins looped over a rail in front of the grocery store at Lone Butte, while their riders, cigarette smoke pouring out of their orifices like stovepipes sticking every whichway out of a bush shack, went in to pick up some groceries. In other parts of Canada, people were using cars for that kind of thing: both to smoke up the air and to get themselves to it. It was, after all, the 1960s. The country was on the move. Before we knew it, it was 1967, and every primary school class in the country learned to sing about it:

Ca-na-da!

One little, two little, three Canadians!

We love thee!

In the Cariboo, though, up high on the Plateau, people found their own use for cars. They stuck to it, too.

Coralling cars on the shore of a Cariboo Lake at 70 Mile, 1992.

Al thought the horses were all pretty funny, and he built a whole literature of irony out of his response to them. Art imitates landscape. There’s enough irony in the Cariboo to keep any functioning society going for years.

It’s not just the Cariboo, though, you know. Look at what the Welsh had to say about it, way back, even before the English moved in:

It was hard to get around the stringy, pointy sheep fence surrounding this dolmen, and the sheep shit, too, to get the hill and the hill-shaped dolmen lined up just right, but I think you can get the idea. Sheep! Don’t tell me about sheep. They lie dead beside the road in Wales. None of those Cariboo snake fences for them there! If you’re not a sharp sheep in Wales, you’re a dead sheep.

Here we all were, hunkered down behind our mountains and rivers, happily slipping back to Eden, when Al came into town and ruined it all.

I’m not joking. Two years after Al Purdy wrote The Cariboo Horses, a man received a Canada Council grant to go up on top of Fairview mountain among the blackflies blackflies blackflies and the abandoned mineshafts and write poetry. Canada, like Wales, had a sure and strong desire for poetry in those days. Well, in Canada’s case, it was more a matter of nationalism, but, hey, poetry has proven itself over the centuries as being one heck of a great way to stir up the nationalistic juices. We should have known better, though.

Three years later they were either tits up with the Welsh sheep or were fomenting a revolution. As far as nationalism goes, this is called evolution.

When the poetry did not come in a Tennysonian torrent, he eventually moved down off of the mountain. That was at the end of the 1960’s, when the poet, Charles Lillard, moved out of the bush and saw a young Tsilq’otin woman riding a horse across the white glacial water of the Taseko River on the western edge of the Chilcotin Plateau. She looked at Lillard with complete disdain. This, too, is called the evolution of nationalism.

The poet Charles Lillard meeting the natives and turning away from Canada, realizing that if there was any answer for us, it had to come from ourselves, not from the outside world, although the outside world was certainly doing its best to come in. Canada’s sovereignity over the Western half of the Plateau has not yet been acknowledged. In fact, the Supreme Court of Canada has even announced that the land there does not belong to Canada, that it has no jurisdiction over it, except the obligation to work out the terms of its relationship to the rightful owners. This, too, is called the evolution of nationalism.

Two years after Lillard looked across the Taseko River and saw what was humanly possible, the blackfly poet of the Similkameen was recovering from brain surgery by talking to me slowly in the hot Cawston sun, while I grafted his apple trees. He wanted to plant an orchard for his three-year-old daughter, who would soon survive him. Five years later, cancer invaded Lillard.

Sometimes people in isolated areas get the weirdest ideas. Out in the Irish Sea, off the coast of Wales, lies the Island of Anglesey, where local legend holds that 10,000 saints are buried, where the Christian Church got its start three and a half centuries before it got its legs underneath itself in Rome.

The tides of the Irish Sea break against it like the waves curling off the bow of a ship. You can just make out Ireland in the background to the right. The shot was taken from a gun emplacement on the Welsh Coast, a bit of memorabilia from the Second World War. You just never knew what was going to pop up. The day I was there, the sun was shining, but I did have to watch where I stood amongst the sheep shit, yes, and on the way out there it seems I was almost run over by a nun, with a determined glint in her eye, as she raced her little blue car along a narrow sheep-shit lined road. There are, it seems, precious few fences in Wales, and when they show up, people don’t rightly know what to do with them. I love Wales.

Some poets like fences, though. Here’s what Matthew Arnold said about them at Oxford, when accepting the chair of poetry:

And I shall not, I hope, be thought to magnify too much my office if I add, that it is to the poetical literature of an age that we must, in general, look for the most perfect, the most adequate interpretation of that age, — for the performance of a work which demands the most energetic and harmonious activity of all the powers of the human mind.

In poetry? You gotta laugh. Oh, unless Arnold meant this:

A page from Dean’s Royal Moveable Punch and Judy, a Victorian children’s book (c. 1870)

The people are not amused.

Arnold didn’t have to worry much about what the people thought, perhaps, but we do, these days, because the result of all this irony, all this disconnect between the lives we live and the words we have with which to speak of it, is that we are being replaced. Even the tools I used on the farm as a kid are now turning to rust. Even the computers that are stacked up in the cupboard in my garage and on the landing of my stairs, a precarious pile of slate grey plastic moulding, mouldering like old leaves, has become obsolete. Modernism, the whole industrial project that was going to give us the tools with which to live better, richer lives, is on the way out.

building Adam in the Garden of Eden

A Souvenir Postcard from the Hermann Denkmal in Germany, c. 1914

Matthew Arnold forgot to save his work.

Now, if you’re anything as lucky as Arnold is with stemming the tide of popular revolution, or, God help you, anything as luck as I am with computers, you will have forgotten, at times, to save your work, too. You, too, will have sat in heart-racing despair as the hard drive crashed and everything you had worked on so hard for the morning had become irretrievable, at worst, or mind-numbingly, time-destroyingly hard to retrieve, at best, when you could have, like, been writing a poem or something, right. You feel so helpless. Really, now, that’s silly. I’ve always said, that every computer needs to come with an emergency kit, like those little red fire alarms in school hallways that someone is always pulling when there is no fire, just to hear the bells ring. It could be covered with a glass plate, and just like those irresistable, strawberry-licorice-coloured jobs in school hallways could say: In Emergency Break Glass. You would not feel so powerless in front of your machines. I figure that’s worth something. I figure that’s worth a lot.

It would be possible, I think, to also use it on your TV. Dishwasher, Stove, Refrigerateur, Microwave, heck, even on your car.

To the winds with planned obsolescence!

The scene that sticks with me from the movie Diner is the one in which Mickey Rourke stops his car at the side of a road when he sees a pretty girl excercising her racehorse behind a white fence. He tries to put the make on her, and asks her name.

“Sally Chisholm,” she says. Rourke looks at her blankly. “As in the Chisholm Trail Chisholms.”

Rourke turns to his companion and says, “Do you ever get the feeling there is something going on you know nothing about?”

No kidding.

On that note, the movie ends.

On that note, five years ago, Shauna told me about a conversation she had had one morning in 100 Mile House, right here on the Plateau. A friend of hers, a working man, a regular guy in a blue cotton work suit you order from the Sears catalogue, had come to her, asking her to give me a message. Shauna tells the story:

"'It would be better coming from one of his friends,' he told me, after he pulled the door shut and sat down in a chair across the room from me. 'He doesn't deserve to hear it from just anywhere in town.'

'Thanks,' I told him. 'I'm sure he'll appreciate it.' I wasn't sure, but I was curious about what all this was about.

'I'm a Mason,' the guy said. 'We had a meeting last week to talk about membership. Harold's name came up. We spent a lot of time talking about him. People said, 'Look at him. His grandfather was a communist. He cared about people. Harold would be a good Mason.' But then someone else said, 'Yes, but his father, Hans, was a fascist. He was terrible to his workers.' In the end, the group decision was that Harold had mixed blood and we could not afford to take a chance on him. Tell Harold that it's nothing personal.'

"What do you know about that?" Shauna asked me.

"It's incredible," I said. "How do they know any of that, about who my father is, or even about my grandfather?"

Shauna shrugged. "I was hoping you could tell me about that."

No, I can’t. I can tell you about something real.

To noble a pear tree, first select a new shoot the thickness of a pencil from the tree you wish to clone. It will be late July or early August. Trim the leaves on this shoot down to stems 1/2 centimetre in length. This is called your budwood. Second, select a seedling pear tree of approximately the same thickness and cut a T-shaped cut in the bark of the seedling tree, approximately six inches from the ground. The top of the T should be approximately 1/3 the diameter of the tree and the leg of the T approximately three centimetres long. Third, after prying open the two flaps of bark formed where the top and legs of the T meet, hold the budwood in your left hand, with the tip of the wood towards you, and place your knife approximately 1 1/2 centimetres below a bud. Drawing your knife towards you, cut down slightly into the wood; continue drawing the knife until it has cut below the bud to a point 1 centimetre above it. The cut will be easier to make if you draw the knife laterally through the wood at the same time you pull it towards yourself. The cut will only be possible around the hard wood surrounding the bud if the knife is sharp enough to shave with or to cut a loose piece of paper with one light stroke. You might want to take care of that before you start. Complete the cutting of your bud by freeing the bark containing it it by scoring the bark at the top of your cut and lifting the bud free with a sideways motion. Fourth, slide the bud into the opened T on the seedling tree until it fills the cut from top to bottom. If the bud is too long, cut off the protruding part in the cross of the T with your knife. Fifth, beginning at the bottom of the T, wrap the bud snuggly with a 9 cm. length of rubber band, securing it at top and bottom by crossing it over itself in a half-hitch loop. In ten days, the bud will have adhered to the new tree. In two months, the rubber band will rot off. Early the next spring, cut off the seedling tree one half-inch above the top of the bud. When the tree begins to shoot, remove all shoots coming from the original tree, leaving only the shoot growing from the bud you grafted on the summer before. That bud will make your new tree. Depending on variety and rootstock, in about five years it will bear fruit.

Monkish tricks with pear trees to catch a little more summer sun.

Obsolete knowledge? Perhaps. Just after the First World War, the American poet Ezra Pound wrote his Confucian Canto, poem number XIII in a long series meant to imitate an industrial assembly line. So clever, huh! Pound wanted to write a book of poems which would be required reading for any man wishing for a career in politics. He didn’t know about computers. Or, to put it better, he hadn’t yet learned how to think like one.

It’s not his fault, entirely. After all, he died in 1973, and back then, this is what we knew about how computers think:

from The Story of Computers, by Roger Piper, Harcourt Brace & World, 1964

Oh, we know better now, I tell you. Now it’s computers that are looking over their shoulders toward replacement. That sledgehammer? That computer emergency kit? It’s too late.

Thing is, it’s not our hammer any longer. Thing is, we’re no longer at the pinnacle of evolution, or the top of the food chain. Dolly is. You probably know Dolly. Dolly is the sheep cloned in England, using cells from the uterus of a dead sheep. She grew up to be a handsome, bleating animal, frisky as the day she was born, but, alas, Dolly’s cells were old. It seems that a living cell can only divide so many times before it starts making mistakes, like a computer, might I add. Ah, Dolly had her dreams, there on the top of the food chain.

The American composer Steve Reich revisited the sampling techniques and rhythms of his 1980s masterpiece about the Holocaust, Different Trains by composing a new piece in comemoration of Dolly’s plain blind bad luck outside the fence of the Garden of Eden. Instead of sampling trains, German and American, and American conductors and Holocaust survivors, instead of talking about “Black crows, black crows were invading my country. Black crows were invading my country,” in the rhythms of the rails, he sampled scientists speaking about their work with Dolly. “I can’t wait to get a new body,” said one of them. “We are all machines,” said a second. “I have no difficulty with the idea of pulling the plug on any machine,” said another. Reich constructs his music around their voices. Dolly is transformed into a child. It laughs with its mother. Have a look and listen, here. Your life depends upon it.

During the Second World War, still embittered by his experience with the culture of World War I, Ezra Pound broadcast rambling speeches on Radio Rome, exhorting the G.I.’s of the American Army to quit the war by speaking to them about the poetry of ee cummings. He praised cummings’ literary report of a journey to Russia as a credit to the American race.

"The American Race!"

Here, you might need this:

On the day Germany declared war on the United States, Ezra Pound urged American soldiers to conquer all of North America, including Canada, and to leave Europe to the Europeans.

December 7, 1941

Radio Rome

Ezra Pound Speaking

Anyhow, I have, in principle, NO objection to the U.S. absorbin’ Canada and the whole NORTH American continent.

Thanks, Ez. Here’s a little something for you, too:

Hip Dysplasia, though. Check out those bad hips. That’s what inbreeding gives ya.

When Pound made his broadcasts over Radio Rome, unknown to him, unknown to everyone except for three men, the German Post Master General and his assistant had constructed a nuclear bomb in their basement in a Berlin suburb. The third man did not believe them. When the Post Master General brought the idea before him, Hitler scoffed, and said, “Oh, now my Postmaster is going to tell me how to win the war!” The idea was that the A10 Rocket could carry it across the Atlantic and drop it on New York. It would have won the war, all right.

Tune back next week for some speculation on that and on the Byzantine politics of Aryan Physics. Aryan physics? God, yes.

Computer Built in Accordance With the Analogical Laws of Aryan Physics

If you fill a vessel with water to a specified level, then lower this cast pyramid into it to a predetermined mark, you can read off of it the cube root corresponding to the volume of water displaced by the pyramid. For this, you don’t need Quantum Physics.

Your host next week, that Sumo Wrestler of Quantum Physics: Schrödinger’s Cat.

To prove that there was something wrong with regular (aka Aryan) physics, in the 1930s the Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger proposed that a cat randomly killed in a sealed box would appear neither alive nor dead until the box was opened, that, in fact, you could not tell when the cat had died: during the random release of cyanide, or when the box was opened and the cat was observed to be dead (or alive). This, said Schrödinger, was silly. He suggested we needed a better physics.